Wildlife – John Aston

Wildlife –John Aston – February 2026

See also Walks and Fishing

Cod Beck

Even if you’ve never been to Thirsk before, you can’t miss the Cod Beck. Smaller than a river but bigger than a stream, the beck enters Thirsk through Norby, runs next to Millgate car park, then under Bridge and Finkle Streets before leaving town through Sowerby. The beck might look unremarkable, but it is a haven for wildlife and has some unique characteristics. It rises on the North York Moors near Osmotherley but it is a tributary of the River Swale, which has its source nearly fifty miles west, above Keld, in the heart of the Pennines. The beck’s catchment has relatively low rainfall, but the Swale’s is much higher, which can create flooding on the lower Cod Beck around Dalton, even though it may not even have rained here.

Although the Cod Beck tumbles quickly off the western edge of the Moors, most of its 23 miles are taken at a gentler pace, as it meanders its way across the quiet countryside surrounding our town. It is a shallow stream, often no more than knee deep and only rarely more than four or five feet, but it supports a host of wild life. In this series of short articles, I will highlight the flora and fauna you might see on, or near, the Cod Beck through the seasons, from the wild garlic of early spring to the colourful Dames Rocket, Goldenrod and Meadowsweet which cover the Beck’s banks in Summer. There’s a lot of wildlife on the Beck, and if you keep your eyes open, you’ll see more than enough to fill a whole episode of Countryfile – really.

The fish

I’m a lifelong angler, so I will talk about fish first – and you’d be surprised how many different species make the beck their home. Although pollution incidents are not unknown, Cod Beck is a healthy water supporting a diverse ecosystem. Above Thirsk, the commonest species are brown trout and grayling. From Thirsk downstream, chub and dace are the dominant species, with the occasional pike and barbel, as well as thousands of minnows. But we get some visitors from much further afield, and none travel further than the eels which start their lives in the Sargasso Sea, 3000 miles away. An eel might live in the beck for decades, growing to well over two feet long before returning to the sea again. Eel populations are declining, but nobody is sure quite why, as they are incredibly tough creatures that can survive even in seriously polluted waters. Lampreys look very similar to eels but have a very different lifestyle, as they live in the North Sea and, in early spring, having already swum up the Humber, Ouse and Swale, they visit the beck to spawn. Keep your eyes open and you might see a writhing mass of mating lampreys, with the males moving stones and pebbles away with their mouths to enable the females to lay their eggs in fine gravel.

In recent years even the occasional salmon has been seen in the Cod Beck. They are rare visitors to the Swale, and even rarer to the Beck, but there is still a chance of seeing one, especially in late autumn, the time when most salmon run up our rivers. The last one I saw was lurking under World’s End bridge in Sowerby on a cold December day, and he’d have swum there all the way from the North Atlantic.

Kingfishers

The brightest star of the Beck just has to be the kingfisher, and how I wish I had a pound for every time I have been told that kingfishers are very rare. They are, in fact, quite common, but you have to be either in, or right next to the water to see them. Kingfishers don’t like flying over dry land, preferring to fly a few feet above water level - unless they see a wading angler. The kingfisher will then make its trademark beep beep alarm call before swerving over dry land to overtake their rival. Kingfishers live almost exclusively on minnows and the young fry of other species, hunting for them by perching on an overhanging branch to spot their prey before diving vertically to catch them with their sharp beak. If you are really keen to see a kingfisher, the best place to do so locally is at Brawith bridge, two miles north of Thirsk. If you can spend half an hour there in late spring or summer, there’s a good chance of a sighting. No guarantees though.

Flooding

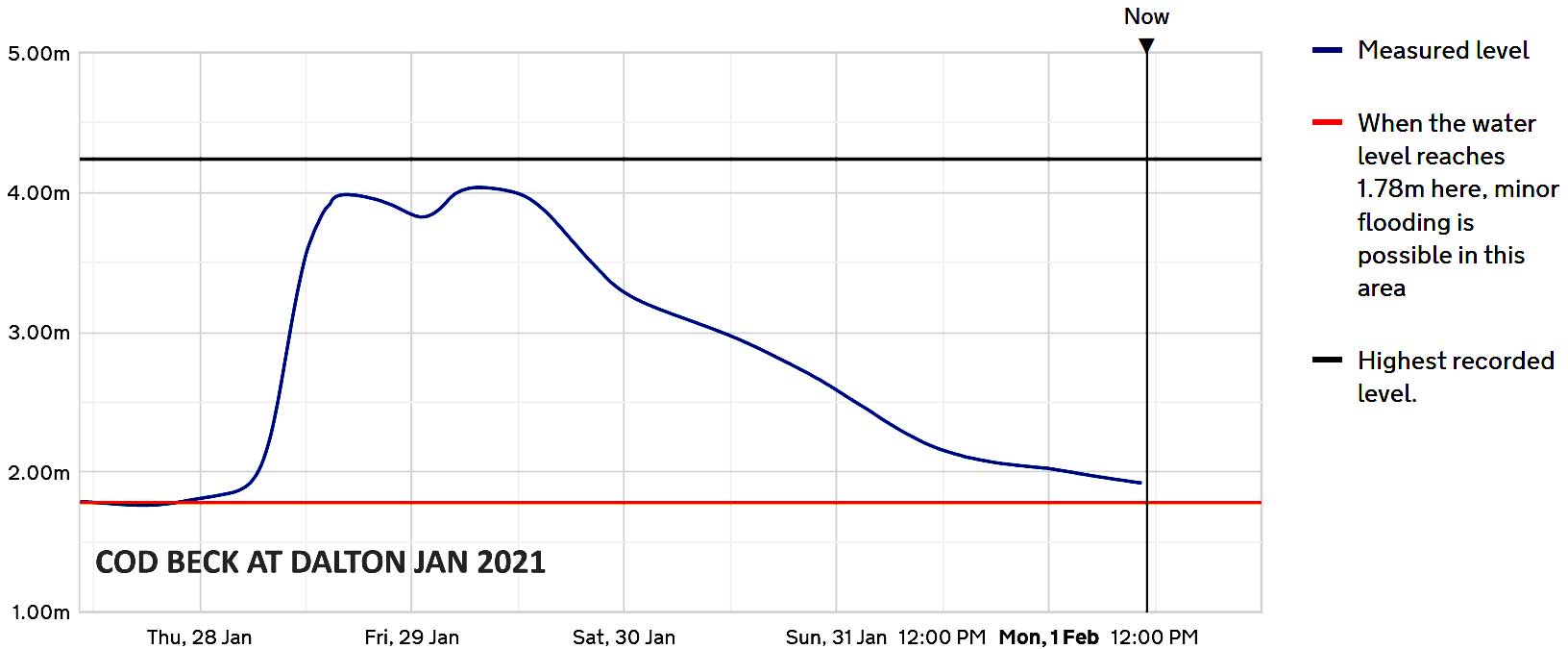

If you need to find out about flooding risks, the Environment Agency has two monitoring stations on the Beck, at Norby and Dalton. It’s also worth checking on the level of the Swale at Crakehill weir, near Topcliffe – you might be amazed to see not only how much the river it can rise (five metres isn’t unusual!) but how quickly.

These links show current levels and flooding risk:

Birds of the Beck

If you only know the Cod Beck from its meander through Thirsk, you might imagine that it is home to lots of ducks but little else. The beck around the Millgate car park supports a population of Mallards, with the occasional white Aylesbury amongst their number, all tempted by the titbits on offer from both locals and visitors. It’s not only people who can suffer from obesity on a diet of pizza and fish and chips… But either side of the town centre, the beck and its flood plain have a rich diversity of birdlife. Some species, such as Swallows and Martins, are seasonal visitors but others live here all year round. In this piece I’d like to highlight some of the birds you might encounter.

One of Britain’s biggest birds, the Grey Heron, is a regular sight on the banks of the beck and on flooded fields nearby. It is a huge bird, with a wingspan of nearly two metres but it is also very shy, and will often take to the air at the first glimpse of a human in the distance. Our local herons spend most of their time on the banks of the beck, watching and waiting patiently before using their long beak to stab small fish (including minnows and young trout). I once had a very close encounter when fishing a quiet pool near Thornton Le Street when, only ten feet in front of me, a heron appeared around the corner of the pool, looking for all the world like a small grey man. The heron squawked furiously, flapped its huge wings and nearly crashed into the tree canopy. I will admit to very nearly having done exactly the same.

Until the last decade, Little Egrets were almost unknown in North Yorkshire but they are now an increasingly common sight. They are smaller than their close relation, the grey heron, but bigger than most other birds you will see on the beck. White all over, with a black beak, they are unmistakable. The footpath leading south from Sowerby, just below the A168, has had a resident little egret most of the winter.If you ever see a huge, heron-sized egret, then congratulations, because you’ve just seen the latest newcomer to the area, the Great White Egret. I saw my first this winter, at Kiplin Hall near Scorton.

At this time of year, the beck attracts a lot of winter visitors, especially various members of the thrush family. Even the Blackbird in your garden may have spent its summer in Scandinavia, but the most noticeable winter thrushes are Fieldfares and Redwings. They are gregarious birds, with flocks of several hundred being common sights. You will need a bird book or app (try the free Nord University Bird ID app) to tell them apart, and at the time of writing, in late January, there is flock of several hundred fieldfares on the fields to the east of the beck a mile south of Sowerby. But don’t blame me if they’ve moved on when you next walk down there…

Raptor watch

Raptors are birds of prey which seize and then carry off their prey – which might be another bird, a small mammal, amphibian or reptile. Because the Cod Beck provides cover and habitat, sightings of raptors are common over, or near the beck, especially away from Thirsk town centre. But you don’t need to go far, as a short walk from Norby upstream, or downstream from the Thirsk and Sowerby Leisure Centre can offer excellent opportunities to spot raptors.

The three species you are most likely to see are buzzard, kestrel and sparrow hawk but red kites are becoming increasingly common locally, and there’s even an outside chance of seeing rarer species such as hobby and even osprey locally. If you enjoy evening walks, you also have a good chance of seeing, or hearing owls – especially tawny and barn owls.

Buzzards are big, vocal and like to show off their flying abilities. They are one of the UK’s biggest raptors, with a wing span of up to 1.4 m, but , despite their size , you will often hear a buzzard long before you see it. Their call is unmistakable, a repeated ‘mewing’ sound which can be almost gull like, and it is often repeated for several minutes. Buzzards tend to soar on thermals, constantly looking for prey and, thanks to their extraordinary eyesight, they can fly up to 1000 feet high and sometimes much more, but they can still spot prey below them. They can be social, with groups of four or more showing off their aerobatics to each other. Buzzards range in colour, but are typically a medium shade of brown above and a much lighter shade below. If you follow the public footpath on the east side of the beck, down from the A168 bridge in Sowerby you will usually see and hear buzzards.

Red Kites are regular visitors, looking very like a buzzard but distinguished by a long forked tail. They often hang almost motionless, high in the air, looking for rabbits and other prey. Once almost extinct, kites are making a comeback, and the birds we see are probably descendants of those released at Harewood in 1999.

Most people are familiar with our commonest falcon, the Kestrel, because they hunt by hovering about 50 feet up , searching the ground for mice and voles. When they spot their target, kestrels plummet (or ‘stoop’ ) vertically to capture them. Kestrels are reddish brown, about 50cm long with a wingspan of up to 75cm. When not hunting they are commonly seen resting on trees or overhead lines. The walk by the beck between Norby and South Kilvington is an excellent place to see kestrels.

Although a similar size to the kestrel, and common in the area, you need sharper eyes to see a Sparrow Hawk. They fly very low and very fast, often jinking through low branches and undergrowth in pursuit of smaller birds. If you hear birds calling in alarm as you walk along the beck, look out for a blackbird or sparrow with a low flying, fast moving sparrow hawk in pursuit at anything up to 50km/hour.

A final tip – if you want to see birds of prey, the best time is the afternoon, and right up to dusk for sparrow hawks. Raptors tend to be late risers.

Predator watch

From the perspective of 2021 it seems incredible that otter hunting was legal until 1978. By that time, otters were extremely rare, not through being hunted, but from agricultural pesticides, especially dieldrin. Because the otter is a predator which sits at the top of the food chain, it is especially vulnerable to the build-up of toxins. But in our more enlightened times, otters have again become widespread and have been present in the Cod Beck for at least twenty years. You will be lucky to see one, as they prefer to hunt at night, but there is always a chance. I see otters every year in other local streams, and although I rarely see them on Cod Beck I have frequently seen their distinctive foot prints on muddy banks. Their droppings – called ‘spraint’– may also be seen on the bigger stones in, or near the main current. If you are really keen, take a quick sniff, and your nose will be assaulted by the smell of fish. Eels and fish such as trout and chub are the otter’s preferred diet, but they will eat crustaceans like crayfish too. Anglers have mixed feelings about the otter’s return, as although their impact on streams and rivers is fairly light, they can wreak havoc in heavily stocked fishing lakes and ornamental ponds.

Otters are much bigger than many people think – a dog otter can weigh over 8kg, and will be between 95 and 130cm long. Mink are often mistakenly identified as otter, usually by people who have never seen an otter, as there is a big difference in size. Mink are darker than otters, often almost black, and are only half the size and a fifth the weight of an adult otter. Mink are native to the USA but were bred for their fur until the Nineties in UK fur farms. The predecessors of the mink we see today on the Cod Beck are likely to have come from West Yorkshire, where many mink escaped or were liberated from fur farms. Their presence has been a mixed blessing, as they are very adaptable predators, being agile climbers and excellent swimmers. Fish, young birds, birds’ eggs and small mammals are typical prey.

Mink are to blame for the fact that the once common water vole is now nearly extinct in Yorkshire. As a kid I’d see them on nearly every fishing trip, as they paddled slowly across a river, but I have seen the grand total of three in the last thirty years, and sadly not one of them was on the beck. There’s some evidence to suggest that mink numbers are declining, so do keep your eyes open. Mink can’t help being mink of course, and they do have some endearing characteristics – they are endlessly curious, and often not remotely bothered by human presence. I will write in a later article about the best way to watch wildlife, and the need to be inconspicuous, but where mink are concerned, you can forget all that. You can encounter them anywhere on the beck, in town or country, and they are most commonly seen either swimming across the beck, or climbing in the undergrowth on the bank. If you click your tongue, or whistle softly, the mink’s curiosity will often get the better of them, and they will even stand on their hind legs to get a better view of you – just like those meerkats on TV ads.

I can’t guarantee where and when you’ll see otters or mink, but if you keep your eyes open, you’ll be amazed what you might encounter. And do let me know what you do spot.

The Space Invaders

One of the many joys of spring on the beck is the huge expanses of Wild Garlic which grow on its banks. Even if you’re not a plant expert (and I’m certainly not) this plant is very easy to recognise, both from its appearance and its very distinctive smell. The leaves are deep green spears, typically 10-15mm long, and they start to peep through the soil in early February of a typical year, variable by several weeks according to severity of winter.

As the weather warms up, the Wild Garlic’s small white flowers appear and the smell intensifies, especially after heavy rain. It is less intensely pungent than the garlic you’d put in your Spaghetti Bolognese, and maybe even has a hint of chives but, along with wild spearmint, it is my favourite smell of the countryside. It’s a favourite taste too, and now it’s even getting popular in trendier restaurants – remember them, back in the days when we could eat out? My recipe is simple – pick a couple of fresh leaves, rinse them and add them to an egg mayo sandwich. Bliss.

Wild Garlic is native to the British Isles, but the two plants I’m now going to talk about are invasive species, which can cause problems for the environment. And one of them, the Giant Hogweed, can injure you quite seriously.

Here’s a question for you - what have the Victorians ever done for us? Quite a lot, actually, but not all of it was good. Such as their love of discovering new species of plant abroad, and then deciding that a few samples would liven up the English country garden. That’s what happened in 1839, when the first Himalayan Balsam was introduced to the UK, originally to be grown in greenhouses. And now you will find this plant along thousands of miles of British rivers and streams, destroying habitat and contributing to bank erosion and flooding. But it looks so pretty, the bees love it and so do kids, because it only takes a shake of a balsam’s main stem to create a fusillade of flying seeds.

You can’t mistake Himalayan Balsam, and you will find plenty on the Cod Beck. It grows up to 2 metres high and covers every inch of the bank in places. It produces a mass of small, sweet-smelling pink flowers in the summer months, followed by bullet-shaped seed pods in September, which literally explode when ripe. Individual seeds can be ejected up to 4 metres away and often float downstream to create new areas of infestation downstream.

So what’s the problem? Himalayan Balsam prevents anything else growing but it dies back completely in winter. Because it stops other, more robust plants growing, the river bank is much more vulnerable to erosion, and the silt washed downstream can also contribute to flooding. The solution? Despite various well-meant attempts at ‘balsam bashing’ by conservation groups , it only has a minimal effect, because more seeds inevitably appear from upstream and the banks are quickly recolonised. The only solution is to start at the top of the Cod Beck, up near Osmotherley, and to remove, or poison, every single Himalayan Balsam plant. And that won’t be easy…

There’s only ever been one song about an invasive plant species by a Prog Rock band – Genesis, on its 1971 album, Nursery Cryme. “The Return of the Giant Hogweed” is a tongue-in-cheek song about the danger to mankind posed by this Russian plant. First brought to Kew in 1817, it has now spread across the country, but outbreaks are often quelled with glyphosate because this plant is a very nasty piece of work. Contact with Giant Hogweed makes the skin extra vulnerable to sunlight and serious inflammation can result, potentially dangerous to children. You can’t mistake Giant Hogweed for anything else, because it looks like a giant cow parsley plant, usually between 2 and 3 metres tall and with a parasol of flowers at its head. There are often outbreaks in this area, but they are rare on the beck – thankfully. If you do find one near a footpath in town, do let the town council know please.

Don’t worry if you’re not very confident in identifying plants - neither am I. But there’s plenty of free phone apps to do it for you. I have the Picture This app on my iphone but others include Leafsnap and Plantifier. Most Android phones already have the recognition app Google Lens.

Just when you thought it was safe to go back in the water

Some people think that pike bite people, but the only time that could happen is if you were stupid enough to put your fingers in a pike’s mouth. Then there would indeed be blood, because pike can have over 500 teeth.

Otter and mink have sharp teeth too, but you will never get close enough to find out. However one creature can give you a very painful nip, and there are hundreds of them living in the beck, even though you may never have seen one. The signal crayfish is an alien invader, originally from the USA, and it has been farmed here for the table since the Seventies. It isn’t a fish at all, but a crustacean which looks like a miniature lobster, and in some cases not so very miniature at all. They can grow up to 20 cm long and are armed with strong claws – have a look at the picture of some claws I found on a local river bank. An otter had eaten the rest of the crayfish, just leaving the claws – try guessing how big the owner of the claws had been. Here’s a clue – the SIMMS logo on my bag is 10 x 2 cm.

Signals live under stones on the bed of the beck, and also in holes which they burrow into the bank. Look for a steep, muddy bank and just above the normal water level you can often see many holes created by crayfish. Their drilling habit is just one of the many problems they cause – in some places where infestation is severe, river banks have even collapsed.

Signal crayfish eat the eggs of trout and other species and cause damage to the beck’s ecosystem by eating small invertebrates such as caddis and mayfly. Worse still, they carry a plague which is killing the population of our native crayfish. A few survive in the beck, but not for much longer I fear. How to tell them apart? At 10cm, and often much less, the native white clawed crayfish is much smaller than its American cousin, and also darker in appearance.

Is it all bad news then? Nature being ever resourceful, some creatures, especially otter and mink, thrive on crayfish, as do fish like chub, pike and perch. Signal crayfish also even eat individuals of their own species, and there is evidence that removal of larger crayfish can actually increase numbers of smaller ones. What about eating them yourself? Not a good idea – you must have a special licence from the Environment Agency, as well as permission from landowners and fishing clubs – it’s much easier and cheaper to buy them in Tesco.

Save the last dance for me

With thanks to Alastair Logan for permission to use his photographs of Cod Beck mayflies.

It’s almost too easy to find amazing wildlife programmes on TV – there’s Blue Planet, Life on Earth, Frozen Planet (and the rest), and Messrs. Attenborough and Packham have become virtual members of some families. But I think that not even HD on a really big TV comes close to the real life in glorious 3D, and in the real world there's the bonus of escaping the slushy soundtrack and the false jeopardy. “Will Prudence the lost penguin chick (cue strings) ever (sob) be reunited with her mum?“

So you can forget all those wildebeest migrating over the Serengeti, you can spare me those irritatingly cute meerkats, because the miracle of the mayfly beats them all. I’m not joking, because what I’m going to describe is a drama featuring birth, death, rebirth, shape shifting and more sex and dancing than even Ibiza’s hottest club night can offer. You don’t need to travel far, because it’ll all be kicking off on the Cod Beck over the next few weeks.

The mayfly is a large aquatic insect which spends the early part of its life in the unglamorous surroundings of the mud and silt at the bottom of rivers, streams and some lakes. They’re picky about where they live and need clean, well oxygenated and cool water to thrive. The creamy white nymphs (as the grubs are called) can grow up to 30mm in length and they subsist on a diet of algae and decaying organic matter. They can live one or two years underwater before things start to get weird, and then they get weirder still.

In late Spring the mayfly nymphs decide to give their lives a dramatic makeover by changing from being an underwater bug to an airborne fly. Having spent their entire lives e crawling through mud in near darkness the nymphs wriggle up to the surface, where a near miracle occurs. Because what happens is that the skin of the bug splits and out crawls a glamorous creature which then unfolds its new found wings and takes to the air. The mayfly is now called a dun and although it cannot eat (and never will do so again) it will flitter around for a day or two, often resting on bankside vegetation.

Its final act is both beautiful and tragic. In an action unparalleled in the invertebrate world – let alone anywhere else – the mayfly transforms itself yet again. Its body splits open and an even more stunning creature emerges, this time sporting wings like filigreed crystal.

And then the great dance begins, usually an hour or two before dusk, when hundreds, sometimes thousands of mayfly spiral in columns twenty feet above the water, rising and falling in an orgy of sex and abandon. It doesn’t last long, as the males die after mating and the females fly back to the water and lay hundreds, and sometimes thousands of eggs. Then they die too, but the cycle has already begun again as the eggs drift to the bottom of the water.

Mayflies hatch in such vast numbers because they are heavily predated, primarily by birds and fish. Birds such as chaffinches and wrens usually notice them first and catch them mid-air, and fish like trout and grayling often become preoccupied with eating them and gorge themselves over the two week mayfly hatch. I once even saw a kingfisher making a terrible mess of trying to catch mayfly in flight – here was a bird which had evolved to eat only fish but on this occasion Darwinism was trumped by opportunism. Fly fishermen love mayfly time but some call it 'Duffers' Fortnight', because it can be so easy to catch trout on an artificial mayfly.

I can’t forecast precisely when and where to see the dance of the mayfly on the Cod Beck. In a typical year the hatch starts in late May, but can be up two weeks earlier or later depending on the weather. A cool spring may mean that the mayfly’s last dance will be in June. But take a walk down the beck from World’s End Bridge on a warm evening in early June and you just might gatecrash the mayfly’s secret ball. Catch one in your hands if you can – they don’t bite or sting – and take a moment to admire its extraordinary beauty and delicacy. But be gentle, and release it quickly – it’s got a last dance to attend …

Litter – ancient & modern

There was some wonderful work going on between Sowerby and Dalton in mid-March 2021, but I’m still angry that it was necessary at all. Community volunteers were collecting litter from the verges and full bags of the stuff punctuated their progress every 100 metres. Most people take their rubbish home, but there are still too many drivers who litter the roadside verges with coffee cups, pasty wrappers and energy drink cans. I don’t really blame the shops or brands, because it is hardly Greggs’ or Red Bull’s fault that some of their customers are thoughtless idiots. And plastic isn’t always the problem we think it is – the world would not function without it – but discarded plastic is a menace. Litter is a problem in the Cod Beck, because it is dangerous to wildlife and its presence is a nasty blemish on the natural environment of the Beck.

I fish the Beck above and below Thirsk but nearly all the litter I see is found downstream of the town, meaning it is discarded in the town itself, from the bridges and riverside car parking. In late March. I noticed that somebody had thrown a road cone in to the Beck next to World’s End Bridge in Sowerby – what exactly was going on in their mind, I wonder? I am sure I am preaching to the converted, but our litter problem is a national disgrace and I would certainly welcome more robust policing of the problem.

Members of Sowerby Angling Society have regular litter clearance working parties and since then they have removed the road cone and lots of other litter.

But sometimes discarded objects can be interesting, and the older they are, the more intriguing they can become. For example, it’s not unusual to find clay pipes in the Beck, sometimes looking as if they had been dropped only minutes earlier, rather than over a century ago. Clay pipes became popular in the 17th century and remained so until the 1920s, when ready-made paper cigarettes replaced them. Most clay pipes were bought already packed with tobacco and, once smoked, they were thrown away. When I find a pipe, I can’t help wondering who smoked it and when, and what life they were leading. I think the same when I find glazed pots and thick glass bottles, sometimes also completely intact.

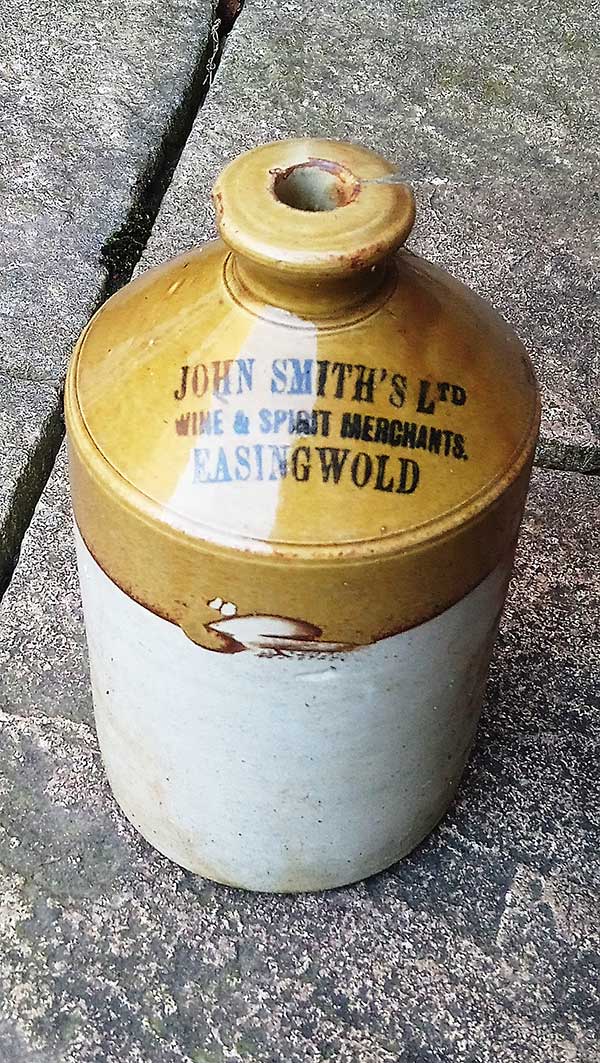

Just above Thirsk, I found a bottle from the Bells Goldsbrough & Co Friarage Mineral Water works in Northallerton, probably about 120 years old. And from downstream, the picture shows an aerated water bottle from Atkinsons of Helmsley – you can just see from the picture that the bottle is engraved with an image of Helmsley Castle. The glazed container pot is from John Smith’s Wine and Spirit Merchants of Easingwold – I found this lying on the bed of the Beck between Sowerby and Dalton.

But the River Rye, just above Helmsley, has some far more dangerous discarded objects – live mortar shells! Duncombe Park was used by the army for training in World War 2, and not every practice mortar shell exploded. I wade the river to fly fish and have found several live shells in the last decade, and the remains of many more which did explode as intended. My fishing club calls in the bomb squad from Catterick to blow the shells up safely. Even closer to home, a nosecone of a crashed military plane, probably from RAF Leeming, can still be seen sticking out of the banks of the River Swale a few miles north of Thirsk.

My best find was also the oldest, and by a very long way. I was fishing on the Cod Beck near Brawith, where the water has carved a deep groove in the fields, with the Beck running up to ten feet lower than its surroundings. Sticking out of the bank, just above water level, was a pair of simply enormous antlers, much bigger than any deer I’ve seen in the UK. Not having a carbon dating machine to hand, I had no idea just how old they were, but I did see some similar looking antlers online, which had been unearthed on a beach in Wales. They were estimated to be about 4000 years old, from the Bronze Age. Crikey…

Cod Beck – sights, smells and sounds

Over the last few months I’ve been writing about the Cod Beck’s natural history and I hope that I have whetted readers’ appetites to enjoy it for themselves. This is my last blog for a while, and this time I want to talk about how to get the most from your own rambles along the Beck around Thirsk. TV programmes like Spring Watch can give the impression that it’s either very easy to see wildlife at close quarters or that only expert TV naturalists enjoy that privilege. The truth is that it only takes a few basic skills for anybody to enjoy the wonderful diversity of wildlife we enjoy.

Most wildlife is easily scared by the sight and sound of people and if you want to get the best from your walks then the fewer people you walk with the better. Groups of people tend to chatter loudly and their chances of seeing anything interesting are remote. So walk alone, or with a friend, don’t wear brightly coloured clothing and don’t talk loudly. If you do see something, don’t point or shout but keep still and say quietly to your friend – ‘what’s the bird at 11o’clock in the big willow?‘. If the bird is moving around in the foliage keep still, because you have a chance of another sighting by spotting the bird’s movement. Which you won’t notice if you keep moving your head…

The most famous fisherman of all, Izaak Walton, had the best advice – ‘Study to be quiet‘

Binoculars help and unless you are a serious birder you don’t need to spend a fortune. But avoid the really cheap stuff too – I’d recommend spending between £75 and £100 but the more you spend, within reason, the better the kit. Avoid very high magnification because anything above 10x is best used on a tripod, and ensure the ones you choose are waterproof because most cheaper makes aren’t. Nitrogen filled models are recommended because they don’t fog up. Using binoculars can be tricky for newcomers as they have a narrow field of vision. If you see something you want to look at, keep your eyes focussed on it and bring the binoculars up to your eyes – it’s much easier than trying to find it by scanning the trees. I keep my own pair focussed for a range of about 20 metres or less – you often get a very short ‘window’ to inspect something close before it flies or runs off. But if you do see a buzzard 300 feet above you, or a roe deer at the distant edge of the field, you have time to refocus.

As for creatures on or under the water, look for ripples on the surface, rings and dimples from feeding fish and movement and shadows under the water. A ripple can come from a water bird, but if there’s a line of bubbles you might have had a close encounter with an otter. Glare and reflections are a problem when looking at the water and polarised glasses (i.e. not just any sunglasses) eliminate the problem. Fish like chub, dace, grayling and trout will feed on insects on the surface and make concentric rings when they do so. Sometimes they will even make an audible splash if they are chasing a big insect like a Daddy Long Legs. Under the water fish can be hard to see but it’s easy with practice – look for movement and shadows on the stream bed.

The Beck has its own sound, even though the A168 can provide an unwelcome backing track. Above the chuckle of flowing water you can always hear birdsong, especially in spring, and each season also has its signature smells – some of them perhaps less welcome than others. With practice you can train your nose and ears to concentrate on the unusual – be prepared to notice the different bird call (was that shriek a jay?) or the new smell (that sudden musky, rabbit hutch smell? It’s where a fox crossed the path before you got up.)

Don’t be self conscious, enjoy those smells close up – the tang of wild garlic in spring, that curious dry nuttiness of willows on hot days, the gorgeous scent of Dames Rocket in early June, aniseed-smelling Sweet Cecily in mid summer and the heady reek of Himalayan Balsam in early autumn. There’s even a name for the heady perfume you often encounter after heavy summer rain – petrichor – and it’s addictive.

And Finally

Don’t think you need to be an expert, or to live miles from anywhere to have the chance of close encounters with the natural world. I am no expert, my only skill is to have learned how to be reasonably observant, but you might be amazed at what I have seen within a few miles of home. Last year I watched an otter swim to within touching distance, and had the special experience of a kingfisher watching me catch a trout from ten feet away. The natural world is free for almost everyone to enjoy – so what are you waiting for?

We can forward your comments to John Aston. Please email news@visitthirsk.uk

MENU

MENU